Plates are thrown and crushed underfoot, as though the family are walking over their own sense of entitlement. The set itself designed by Ian MacNeil, isn’t merely functional, but features an ornate Alice in Wonderland style decorative house, paper-flimsy, which folds out and dwarfs the cast, who crane to enter and exit. It is knowingly peppered with pop culture references: Bernard Hermann’s gorgeously melancholic score from Vertigo augments the film noir-ish flourishes, while the first glimpse of Inspector Goole is oddly reminiscent of the iconic scene of the shadowy figure outside the house in 70s horror classic The Exorcist. The realisation on her face is wonderful, hair and scarlet dress ruffled, providing a sense of glorious schadenfreude to even the most cynical audience member. Sybil is resolute in not believing her family were responsible, until it emerges both her alcoholic twit son Eric (Hamish Riddle, a remarkable comic foil) and Croft were involved in sexual relationships with her, and stolen money was proferred. The stand-out scene occurs in a beautifully performed volley of insults between feline, smug mother Sybil (a fruity, almost camp turn from Caroline Wildi) and Goole, who reminds her that lives of the poor are not something to be dismissed and written off like an small cash discrepancy. But of course, it slowly emerges that he may not be who he claims to be. Goole’s actions are an effective hand grenade, blowing apart any airs of respectability, and undermining middle-class mores. Fingers are pointed, as everyone becomes complicit in her death, from spoilt Sheila (Katherine Jack) her pompous fiancee Gerald Croft (Matthew Douglas) to the bluff patriarch Arthur Birling (Tim Woodward). Most are aware of the story from their secondary school curriculum: an unorthodox Inspector, Goole (a magnificent, exasperated Liam Brennan, channelling his inner-Capaldi in bursts of splenetic rage) arrives at a posh house to inform the well-respected members, The Birlings, that destitute ex-employee Eva Smith has been found dead of an apparent suicide by drinking disinfectant. Perhaps it’s the dead-eyed children and their staring, statue-still parents, positioned to the left – literally- and their steadfast refusal to move or blink.

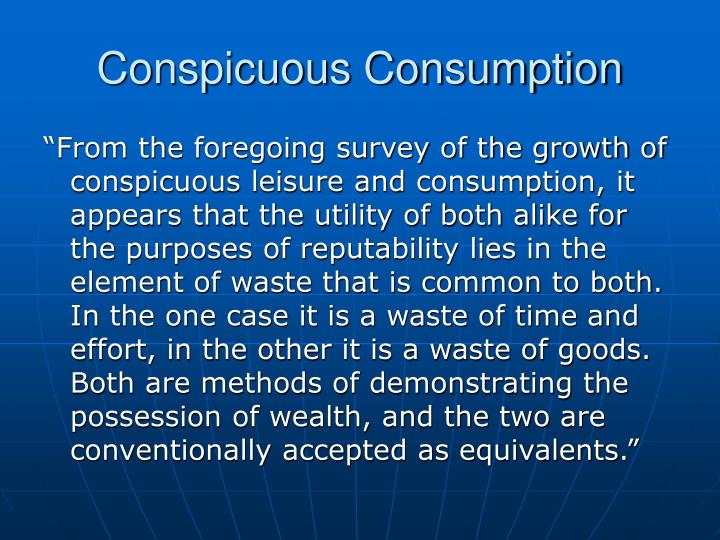

Conspicuous consumption sex work,poverty, alcoholism, Tory (mis)rule et al may seem like facile box-ticking exercises on paper, but there is something insidiously creepy in Daldry’s staging choices. It is unrelenting, an anti-postcard of austere Edwardian Britain which is still worryingly relevant and resonant. Stephen Daldry’s adaptation of An Inspector Calls is that rare find: a postmodern study in reviving a classic which allows it to be seen with fresh eyes.įrom the minute three little ‘guttersnipes’ run onstage in rain and smog (very apposite for a Glasgow audience) to the sound of an air raid siren, tugging at the red curtain and each other, to the final deadly reveal, its bleakness sticks in the ribs like indigestion.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)